Nobody gave me the Ocean’s franchise.

Let me back up. Some of the best art in my life was given to me by someone now rendered inextricable from it. My dad gave me Moonrise Kingdom when I was thirteen and Mad Max: Fury Road when I was in high school, gave me They Might Be Giants and Blondie and Vance Joy. My best friend Leo gave me Katzenjammer and The Raven Cycle. An internet friend I don’t speak to anymore gave me a whole playlist of songs that still come up on shuffle - gave me Dear Reader and Palmcorder Yajna.

The people we love share things with us and when they do they press their thumbs in, make an imprint, unique and indelible. And we wouldn’t have it any other way, right? Even the people with the best, most trailblazing taste must remember how their exes made them watch Wong Kar Wei, listen to St. Vincent, read Colleen Hoover. It’s like a small kindness packaged inside a bid for knowing - I have weighed your heart and found that you could love this.

But nobody gave me Ocean’s 11, or 12, or 13. Like The Godfather, or The Sopranos, or other non-Mafia oriented things, they’ve entered the canon already, and even if nobody tells you to watch them, there are listicles, tweets, trendy scratch-off posters. Incisive cultural critics, two decades of spin-offs and knockoffs and parodies on Community. The Oceans movies permeate the culture.

But like everything that permeates the culture, what I love about Ocean’s 11 is its glorious specificity. Which is to say that since nobody gave me Ocean’s 11, nobody primed me for what it contains, outside the structure of “when you think they’ve lost, they’ve really won.” For example: did you know that Ocean’s 11 contains Cockney rhyming slang, which was taught to me completely unironically as “something we might encounter” on a 2019 study abroad trip to Wales? Did you know in Ocean’s 12, Julia Roberts pretends to be a conwoman pretending to be Julia Roberts? Did you know in Ocean’s 13, Matt Damon has to be dosed with pheromones in order to sleep with a MILF?

I’m getting ahead of myself. I want to show you that the Oceans movies are about something other than what they say they are about. I am trying to give you the Oceans movies, but it’s hard to press my thumbs in.

What I keep trying to hit and swerving around at the last second is how the Ocean’s movies express masculinity in a way that makes me want to be a man. As someone who was born a woman (well actually I was born a baby), grew up a Tumblrina, and slid into the presumed genderqueerness of most people my age, my gender is more of a moodboard than anything. I swallowed the pain of womanhood when Lady Bird did, mourned my own lost archetype with colorblind Paul Dano. In high school I wore a bright-red polyester suit and a Ben Nye black eye to my prom, an expression of - something. Masculine as violent when both things were to me just a costume to put on and take off, never quite convincing anyone. My gender is nothing so much as a series of stories I am telling myself, and being told.

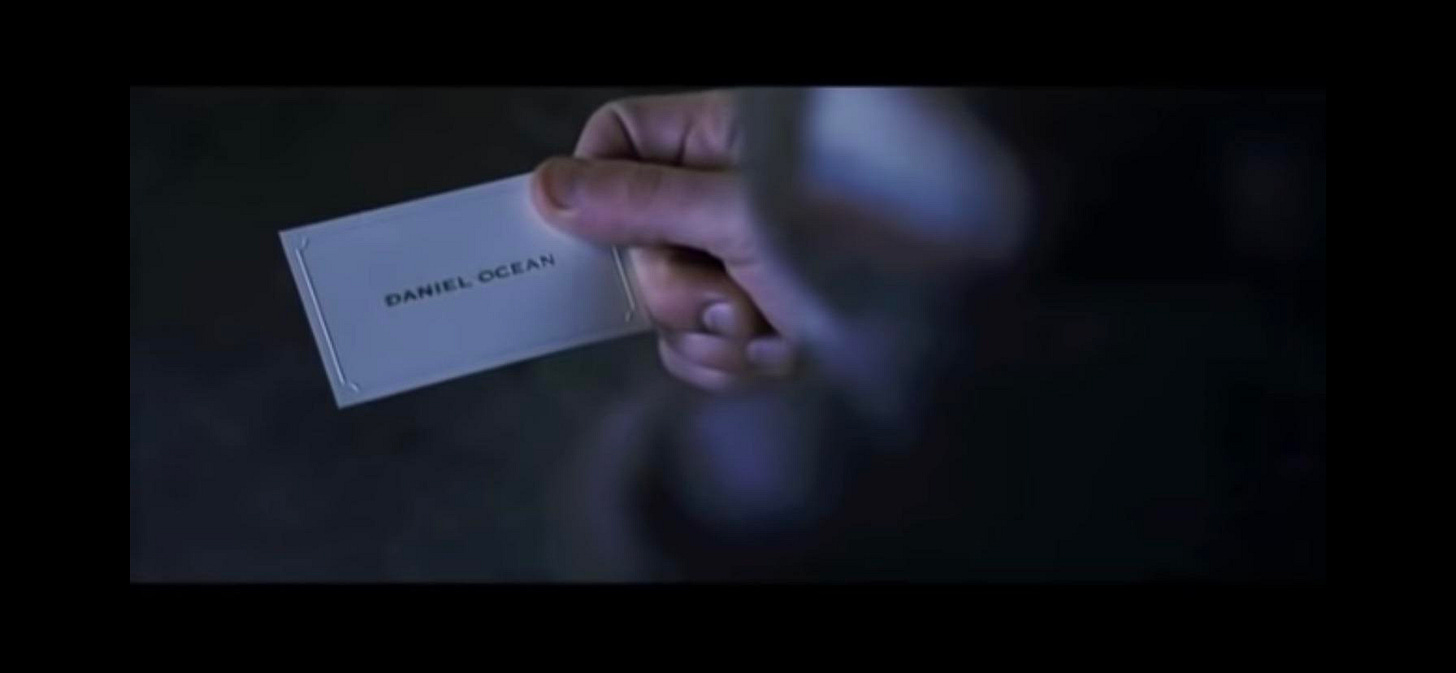

Which is why Danny Ocean’s embossed business cards really do it for me.

Let’s step back again. What does it mean to be a man, as laid out by Steven Soderbergh’s Oceans trilogy?

A man is, first and foremost, cool.

There is no scene in any Ocean’s movie where coolness is not the prevailing ideology. One imagines this draws heavily from the original Rat Pack movie (which I unfortunately have not seen) because the constant confluence of “cool” in its 2001 meaning - suave, detached, impressive, well-dressed, and, yes, sexy - with “cool” in its 1960s meaning - unflappable and very capable under pressure - defines all three texts.

Danny Ocean is always in control of the situation. He understands Mandarin, but only ever speaks in English. He drinks whiskey, but never more than a tasteful glass. Insofar as characters in Ocean’s movies have arcs, they move slowly from uncool to cool, with Danny Ocean always there to mentor, to jab softly, to draw a line around “cool” and invite them in (as he does with Saul) or keep them gently but firmly on the outside (as he does with Linus).

If the Oceans movies are to be believed, all of these men are millionaires, but to use a cliche, for Danny, Rusty, and other figureheads of masculine ideal in the Oceanverse, wealth really does whisper. Their cars and clothes are always old, harking back again to the 1960s, an era of mob bosses and newly-adult baby boomers demanding their own adultified youth culture through muscle cars and crushed velvet and, okay, a lot of sex, as the Hays Codes gave way to the (credit to Karina Longworth) Polly Platt’s Dumb Ex-Husband Era.

A man always understands, never contorts himself to the situation. A man can always access sex, but might prostrate himself for love. A man is well-dressed, thinks nothing of it. A man wears a suit to county jail, just so that he can put it on again when his time is up, bow tie undone, ready for anything.

A man respects that which came before.

This is deeply related to what the text presents as “cool.” Danny robs the Bellagio in Ocean’s 11 because its owner-operator is fucking his ex-wife. In 13, a new casino proprietor has cut out Danny’s friend from a new venture - rejecting Vegas legacy in favor of modernity.

What’s interesting about this is its blinding ahistoricity. Las Vegas is perhaps the one American city I associate least with respect for the past. Las Vegas is the one city in America where you can visit a 100 meter tall eyeball orb for literally no reason. It’s a monument to man’s hubris, a metropolis of the dunes, hundreds of miles from where any city should reasonably have been built. It is constantly dying and being reborn from its own stupid technocratic Kesha-and-David-Blaine ashes, and that’s why we love it.

But the Oceans movies are firm in their fidelity to the past - what came first is rightful, is sacrosanct, is, yes, cool! My favorite place where we see this is in the script for Ocean’s 12, which is funnier and much nerdier than either its forebear or its offspring. Ocean’s 12 is a constant debate about how to run an Ocean’s scheme, and each tactic is named, loved, even. They’re going to run a Baby Makes Three, a Red Balloon, a Slide-and-Whistle. We, the audience, don’t get context on most of these, but what we do see is a brief window into a canon of crime that our heroes are not just in awe of but actively study. True, there’s a gap between how much open adoration of others we see from Danny - a very small, very tasteful amount - and from Linus - so, so, so much - but no character is a self-made man. They are all standing on the shoulders of titans, thieves that came before, Old Vegas financiers, their parents, Sammy Davis Jr.

A man builds community with other men, and withers without it.

This is the reason I wanted to write this essay. For all the things the Oceans movies are about as texts, they are about male friendship perhaps most of all.

And I don’t want to slide into gender essentialism here. The men in Ocean’s 11, 12, and 13 don’t act the way they do because of their dicks, the same way the girls in The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants don’t act the way they do because of their vaginas, or their magical jeans. No - it is a social reality now, and was even moreso in 2001 (to say nothing of 1960) that men are not socialized to build community with one another, at least not by media. And to an extent, nobody is, under capitalism, but while the Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants write each other letters about their inner conflicts and sexual misgivings, men on film are less likely to use each other as an outlet for emotional catharsis. In one study from 1996, it was noted that women give 2/3 of all compliments, and receive 3/4 of them. (For more, see Janet Holmes.)

What men have instead are two things: archetypes that actually serve rather than undermining their power (women get more of a Madonna/whore dichotomy thing) and the community afforded by shared skill, shared labor, and shared interest. Masculine communities exist everywhere - there are a dozen men in the basement of my local Parks Department Y, playing with electric trains on a huge rig. There are men on Reddit inventing new languages of humor and self-policing. There are men who enjoy NASCAR together, basketball together, poker together (all three of these are motifs in Oceans and other Soderbergian explorations of masculinity, like Magic Mike and Logan Lucky). There are men who, yes, still dress up as Deadpool and go to conventions in mid-size cities and say Chimichanga to each other, and we must imagine them as happy.

Briefly - so briefly, I promise - I want to talk about Dead Poet’s Society, which is another movie about how men, well, men who are still boys, navigate this lack of community. The boys at Welton are children, and as children do, they engage in various forms of play together. Form study groups. Build a radio. In the movie’s inciting incident, though, they make a bid at real, adult community - the titular Society - and in it they find an actively non-gendered form of community enrichment. They make art. They speak about and gesture toward sex, and love. A metatextual reading tells us that they even explore homosexuality with one another (check my ao3 account for more information on this) in a way that would be aggressively repressed and rejected by mainstream adult society. But it is mainstream adult society that ultimately steps in, takes over - first Knox, then Charlie, then poor, sweet Neil, and although triumphant (and frankly quite beautiful) music sounds over the end credits we are left with the knowledge that these boys, now men, will never have something like the Dead Poet’s Society ever again.

What does await them as adults, if they are lucky, is the kind of male-male bonding expressed by Ocean’s. It’s always mediated - in 12, which I do think is the strongest of the three movies, even explicitly emotional conversations are mediated by The Oprah Winfrey Show, itself too feminine to discuss openly. No, the Oceans crew discusses above all else, work. But just like lingerie is sexier than nudity, these bids for connection express a much deeper understanding of masculinity than most contemporaneous work. Because these men are cool, are archetypal, are doing the actual work of building community, they both must express their fears and insecurities to one another and are forbidden from doing it directly.

Danny Ocean stands on the train platform - anxious about his wife, about the mobster who is trying to kill them, about his friend Yen who has been driven in a duffel bag to the wrong country, insecure in his skill as a thief and upset by his changing social reality as Rusty, his only confidante, enters into an ill-advised affair - and he asks how old he looks. His friends bumble through their replies. Mid-fifties, maybe, but “only in the face.” None of them are equipped with the tools to speak about what is really happening. But none of them can avoid it, either.

Linus and Livingston anxiously plan how to make their theft, the one that will pay off their murder-debt, and they run through a list of tactics, both already familiar with each. A looky-loo. A driving miss daisy. They don’t say I’m scared - I feel inadequately prepared for this - the loss of my mentors would deal a blow to my confidence in this industry that I do not trust I could recover from. Chalk this up to good filmmaking, and it is! We would get less out of a movie where everyone just says what they’re feeling, all the time, never lies or makes a bad decision. After all, we humans don’t move through the world like that.

Community is fractured, run-through with unspoken rules on what men can and cannot say to one another. But it is always, always there. There is always someone with a car to pick Danny up from jail, always someone to take care of a wife, help with medical bills and right wrongs. Community predates these men - after all, it includes thieves that came before them - and community will outlast these men - why else would they waste their time mentoring Linus?

Where we see men without community, they are exclusively villains, moguls, “self-made” control freaks who run casinos or one-man thief operations. Sometimes these men can be brought into the fold - after all, there is a very 1960s masculinist respect between men who have “made it.” Other times it is them who reject the community and undermine the work of the Oceans crew. After all, the original movie is about a class of World War II veterans, Nazi-fighters, men who built community in one of the last acceptable spaces to do so, men whose community actively crowds out the lives they are trying to lead.

So what I’m saying is, it is so unbelievably easy to read aspirational masculinity into the Oceans films, especially when nobody gives them to you. Because they are mine, all mine - perfectly unimprinted in my brain - they map so wonderfully onto my concept of self that I cannot excise them. I’ve always felt unable to separate my gender, whatever it is, from so much else about me: my weight, my age, my own perceived intelligence, my debilitating reliance on narrative as a tool for understanding life. When I watch the Ocean’s films, it’s not that I suddenly CAN extricate my gender - it’s that every impulse in my brain screams at a Klaxon-volume that I want to be Danny Ocean. I want a business card with nothing but my name, a cool distance from my own insecurity, a suit made of Italian silk and an encyclopedic knowledge of thieves’ gambits. I want community with old men and the ability to mentor young men. I want to access the masculine tradition that the actors, characters, artists of Oceans movies use so easily.

But, agonizingly, I have been brought up in the ways of wild girls, and I have to admit: wild girls do it better. Girls laugh and touch and feel everything - girls hold hands and share beds, girls go to therapy to unpack their relationships with their mothers. Girls kiss each other even when they aren’t trying to kill each other. Girls cry, and not just about death.

In the final scenes of each Ocean’s movie, the crew stands and watches the dancing fountain at the Bellagio as Claire de Lune plays over the scene. The meaning of this is obvious, perhaps - each spray of water is not impressive in its own right, but together, with every jet in perfect synchronicity, there is beauty. Synergy, maybe. The music also works to enhance the theme - Claire de Lune is in the habit of isolating each note, and then playing them back all together, once again highlighting the beauty of things once separate coming together. It’s more sparse and haunting than the sort of synth-jazz PS2 dvd-menu music used in the rest of the film, and for good reason. The men don’t speak.

And I want that! And I don’t. And we beat off boats against the current or however it goes. And if you ever meet me in real life, I’ll hand you a business card with just my name on it. And I will give you the art that I love, so that I can know you and you can know me. And we’ll both trans our genders together.

Until then, I will keep trying on costumes.

While reading this I kept trying to copy lines that flayed me but it's impossible when that's every other line. Exceptional job dude! You not only get what makes the movies so good (I think? I haven't seen them lol but now I will) but a very specific gender hell. You really manage to distill ideas into words so well.